[OP-ED] As Aid Dwindles, Dreams Die: The Systematic Erasure of Hope in Cox’s Bazar

![[OP-ED] As Aid Dwindles, Dreams Die: The Systematic Erasure of Hope in Cox’s Bazar](/content/images/size/w1200/2026/01/photo_2026-01-03-18.24.25.jpeg)

By Niyamot Ullah

COX’S BAZAR, Bangladesh — As the sun dips below the horizon of the world’s largest refugee camp, a lethal silence settles over the sprawling, denuded hills of southern Bangladesh. For the more than 1.1 million Rohingya refugees anchored here, nightfall is no longer a time of rest. Instead, it is a period of quiet, frozen desperation. Behind walls of bamboo and thin tarpaulin, a chilling reality sets in: the world’s attention has moved on, leaving an entire generation to freeze in the dark.

As of January 2026, eight years have passed since we were driven from our homes by the Myanmar military regime. Today, we stand at the edge of a “funding cliff.” We are caught in a cruel limbo between a homeland that remains a theater of war and an international community that is increasingly parsimonious regarding our survival.

I arrived in Bangladesh in 2017, fleeing the embers of my home in Myanmar. As a chemistry teacher, I have watched the camps transform from a site of emergency refuge into a permanent landscape of neglect.

Ground Zero of the Humanitarian Crisis

UN Secretary-General António Guterres previously described Cox’s Bazar as “ground zero for the impact of budget cuts on people in desperate need.” His assessment remains a haunting truth. The humanitarian response in Bangladesh is currently on the verge of collapse, a casualty of shifting global priorities.

The gutting of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) budget has stalled critical infrastructure projects. Simultaneously, the United Kingdom’s decision to slash foreign aid to bolster domestic defense spending has left a gaping hole in our operational survival fund.

The impact is felt first in the stomachs of the vulnerable. Since 2023, food rations have been slashed repeatedly. Families now survive on meager portions of rice, lentils, and oil that must somehow last an entire month. Malnutrition rates among children are skyrocketing. In overcrowded tents perched on fragile, landslide-prone hillsides, parents routinely skip meals so their children might have a few extra grains of rice.

A Winter Without Warmth

For the refugees of Cox’s Bazar, life is a daily struggle against the elements. We face worsening food shortages, extreme weather, restricted movement, recurring fires, and the slow erosion of humanitarian aid.

As the climate shifts and temperatures fluctuate sharply, the weakest—our children and the elderly—suffer most. When night falls, the cold air seeps into every bamboo shelter. For seven-year-old Sumaiya, winter means shivering under a single thin sheet. Her mother tries to wrap her in an old scarf, but it is a futile gesture.

“We have no blankets,” her mother told me quietly. “Every night, my children cry from the cold.”

This winter is particularly harrowing because the "safety net" of NGOs and INGOs has frayed. Drastic funding shortages mean that blankets, coats, and warm clothing—once staple distributions—are no longer available. Families who once relied on these essentials now face the frost with empty hands.

The evidence is everywhere. Children walk barefoot on frozen soil, their breath turning to white mist in the morning air. Coughing echoes through the tarpaulin walls as cases of pneumonia and severe respiratory infections surge. Seven-year-old Hasim rubs his arms to keep warm; he has no sweater, no socks, not even a long-sleeved shirt.

“It’s so cold,” he whispers. “I can’t sleep.”

The Ghosts of History

The current crisis is a modern chapter in a long, bloody history. The Rohingya have faced decades of persecution. In 1977, the Myanmar army launched Operation Dragon King, driving 200,000 people into Bangladesh through mass killings and horrific violence.

That history serves as a haunting warning. Two years after that exodus, over 10,000 Rohingya who refused to return to the site of their trauma starved to death in the early camps of southern Bangladesh. Today, with no safe path back to Myanmar, we face a similar, looming prospect: that our deaths will once again be overlooked by a world preoccupied with other crises.

The Chemist of the Camps: A Glimmer of Hope

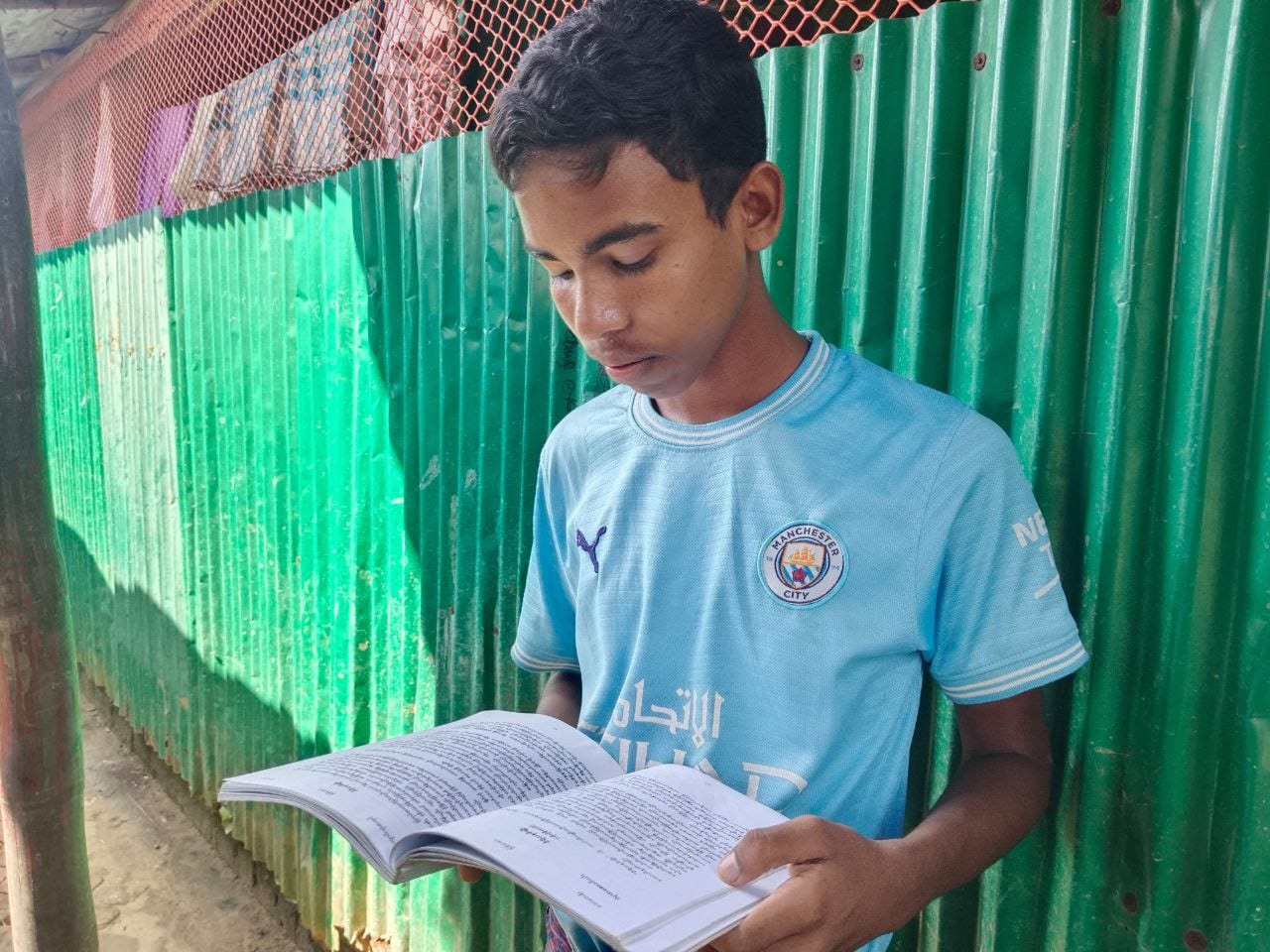

Yet, amidst this deprivation, the human spirit persists. I see it in my student, 18-year-old Yeaser Arfat. Yeaser fled the 2017 genocide led by the Myanmar military under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi. Today, he lives in the same overcrowded, lightless shelters as Sumaiya and Hasim.

Yeaser is enrolled in Grade 11 at a UNICEF-supported informal learning center. He is excited by the hope education provides, but haunted by the knowledge that after Grade 12, his journey must legally stop. In these camps, higher education is not allowed.

As his chemistry teacher since March, I have watched Yeaser prove himself to be exceptionally innovative. Chemistry at this level requires a laboratory, but we have no test tubes, no burners, no chemicals. I use real-life examples from our daily struggles to explain complex reactions. I use YouTube videos on a small screen to show him processes he cannot touch.

Yeaser’s dream is to become a doctor. “In my community, we have no educated doctors,” he tells me. “People suffer more because of our living conditions, but there is no one to treat them. If I can achieve my dream, I can provide lifesaving hope.”

His ambition is born from trauma. Most international clinics in the camp close at night. When a mother goes into labor or a child has an accident at midnight, there is often no one to answer the call. For the Rohingya, every night is a gamble with an emergency that might go unanswered.

The Glass Ceiling: A Demand for Action

The "education ceiling" in the camps is a political creation. The host government’s policy, rooted in a fear of permanent integration, restricts education beyond the 12th grade and mandates the Myanmar Curriculum Framework (MCF)—preparing students for a return that feels increasingly impossible.

Yeaser is not alone. Many Rohingya children dream of becoming engineers, teachers, or leaders. Some have already given up, crushed by the reality of the 12th-grade barrier. But those who still dream, like Yeaser, view education as a tool for survival.

Yeaser’s story is a demand for urgent action. These children deserve the chance to pursue higher education and return those skills to their struggling community. Supporting education beyond Grade 12 is not just about a personal dream; it is about giving an entire people the chance to heal and survive.

An Appeal to the Global Conscience

The story of the Rohingya in 2026 is a story of two winters: the physical cold that freezes the limbs of our children, and the diplomatic cold that freezes the funding for our lives.

As the UN chief noted, our survival is now completely dependent on a dwindling pool of aid. If the international community continues to withdraw, this “funding cliff” will become a mass grave. We are not asking for luxury. We are asking for the basics: a blanket to survive the night, a meal to survive the day, and a classroom to build a future.

For Yeaser, Sumaiya, and Hasim, winter is more than a season; it is a struggle against erasure. If a boy like Yeaser can endure genocide and hunger and still dream of serving humanity, then the world has a moral responsibility to stand beside him.

One coat can prevent pneumonia. One blanket can grant a family sleep. And one policy change can allow a talented student to become the doctor his people so desperately need. The world must not look away.

Niyamot Ullah is a Rohingya refugee and a chemistry teacher currently living in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camps.